OPSEC on a Budget: What BadAudio Reveals About APT24

This blog post focuses on APT24, a China-linked intrusion set active since at least 2011. Despite its long operational history, publicly available technical analysis of this group remains limited. A recent Google Cloud report shed additional light on APT24’s activities; however, it provided only a brief overview of badAudio, a distinctive downloader associated with the group.

As a sample of this malware became publicly available, we conducted an in-depth reverse engineering analysis to better understand its functionality, cryptographic design, and operational role within APT24’s intrusion chain.

As a quick reminder: while APT24’s precise affiliation remains unclear, it is widely tracked as a PRC-nexus actor and is often assessed as operating in support of Chinese intelligence requirements. Recent victimology—especially targeting Taiwan and, in some reporting, the United States—is consistent with that assessment.

That said, recent reporting emphasizes APT24’s use of custom tooling (for example, the BADAUDIO first-stage downloader) rather than highlighting common China-linked families such as PlugX or ShadowPad.

Open-source literature on APT24 is still limited (and, at times, inconsistent), so a definitive assessment isn’t possible. There remains a clear open-source intelligence gap.

Reconnaissance phase

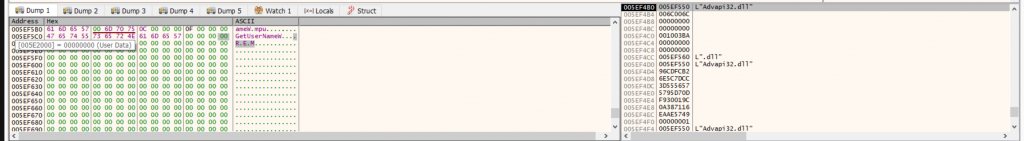

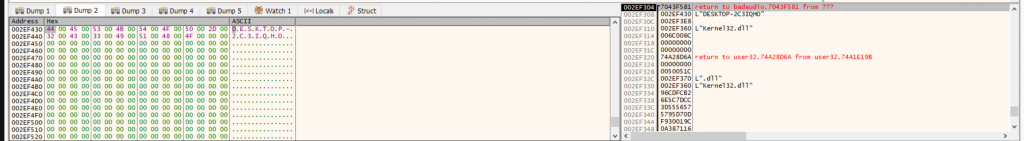

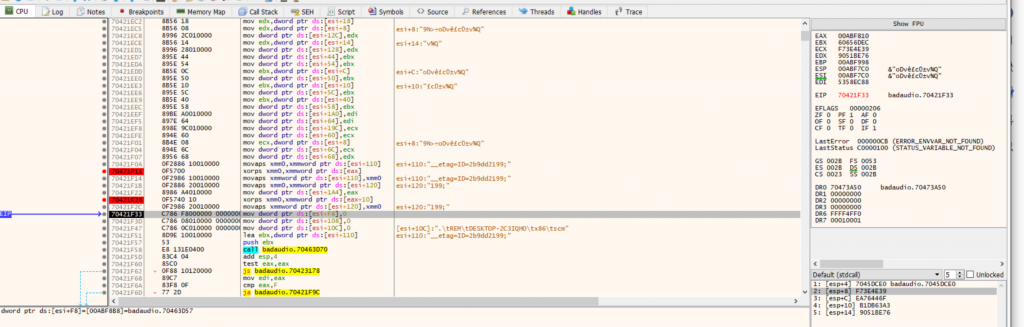

As reported by Mandiant, BadAudio collects host-identifying information prior to network communication. During our dynamic analysis, we confirmed that the malware retrieves the current Windows username via GetUserNameExW, which returns REM in our test environment. We also confirmed that it queries the system hostname via kernel32!GetComputerNameW, which returns DESKTOP-2C3IQHO. In both cases, execution returns to badaudio.dll immediately after the API call, confirming that these values are collected directly by the malware.

Figure: reconnaissance phase of BadAudio using Windows API

The collected host information is then concatenated with an architecture identifier (here, x86) before transmission. In the debugger, the assembled tab-delimited string \tREM\tDESKTOP-2C3IQHO\tx86\tscm is present in memory and later reused during request construction.

Several obfuscation techniques

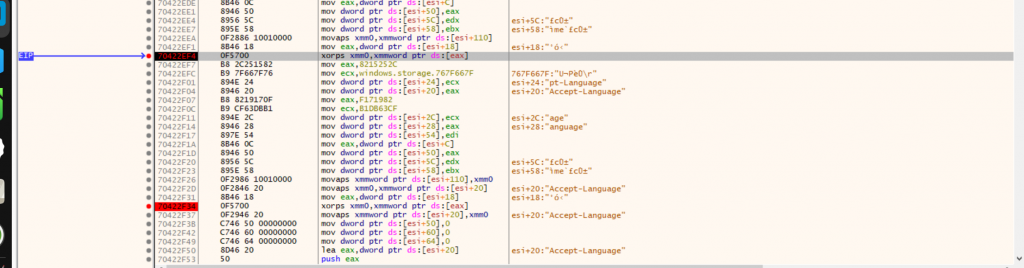

To obfuscate strings, badaudio uses stack strings: it reconstructs obfuscated string buffers on the stack (typically 16-byte aligned) and deobfuscates them in place using an SSE-based XOR mask. At runtime, it performs 128-bit XOR operations in XMM registers (e.g., movaps/movups + xorps), overwriting the stack buffer with plaintext only immediately before the value is consumed.

The malware reuses this SSE XOR primitive across multiple deobfuscation sites with different mask sourcing models. In some cases, the obfuscated string material is built in stack-resident buffers and XOR-unmasked with a 16-byte mask supplied indirectly via a pointer (e.g., [esi+18]).

Figure: XOR-unmasking with a 16-byte mask supplied indirectly via a pointer

In related header-construction paths, the stack buffers are partially populated with runtime-derived context fields (e.g., values copied from [esi+10] and other frame fields) prior to the same SSE-based 16-byte XOR unmasking step (e.g., xorps xmm0, [mask] / xorps xmm0, [mask+0x10]):

Figure: stack buffers partially populated with runtime-derived context fields

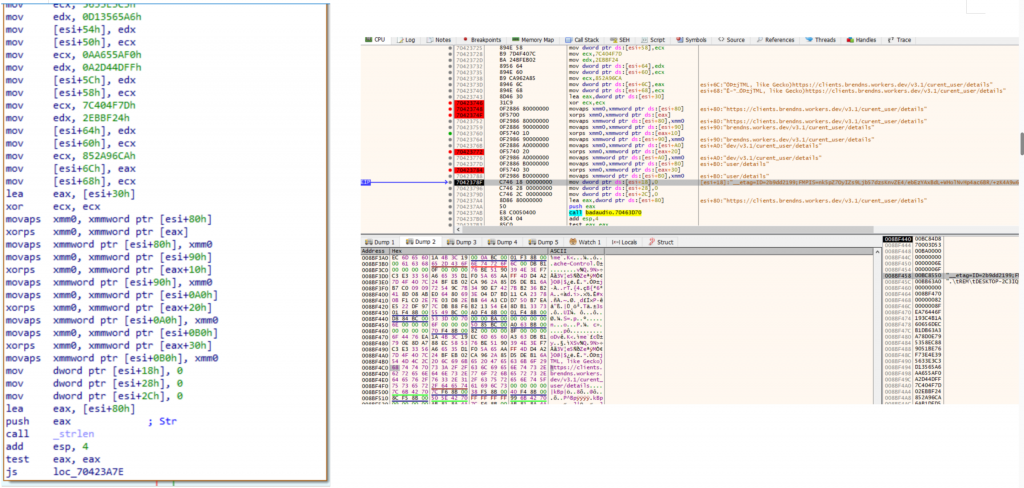

Across multiple observed strings, this 16-byte mask matches the first 16 bytes of the C2 XOR mask, indicating mask reuse across string families. In other cases—such as the C2 URL—both the ciphertext and the XOR mask are hardcoded as immediates, reconstructed locally on the stack, and decoded as multiple 16-byte chunks (e.g., 64 bytes decoded via 4×16-byte xorps operations).

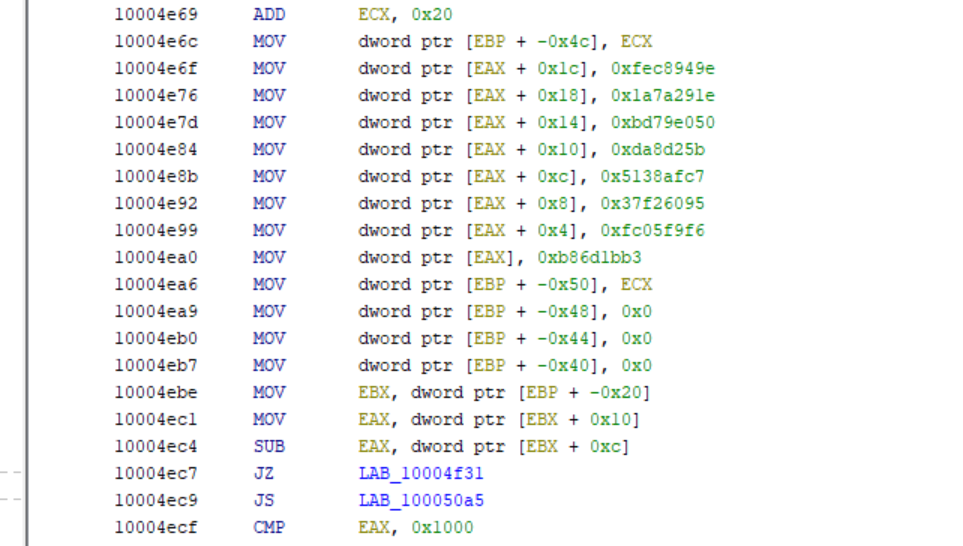

Figure: C2 deobfuscation routine (IDA and x32dbg)

C2 XOR mask reconstructed in memory (64 bytes):

6F 44 76 EA 1A 4B 3C 19 EC 6D 65 60 A3 63 DB B1

79 0E 8D A7 88 EC 58 53 76 BE 51 90 39 4E 3E F7

C3 E3 33 56 A6 65 35 D1 F0 5A 65 AA FF 4D D4 A2

7D 4F 40 7C 24 BF EB 02 CA 96 2A 85 D5 DE B1 6A

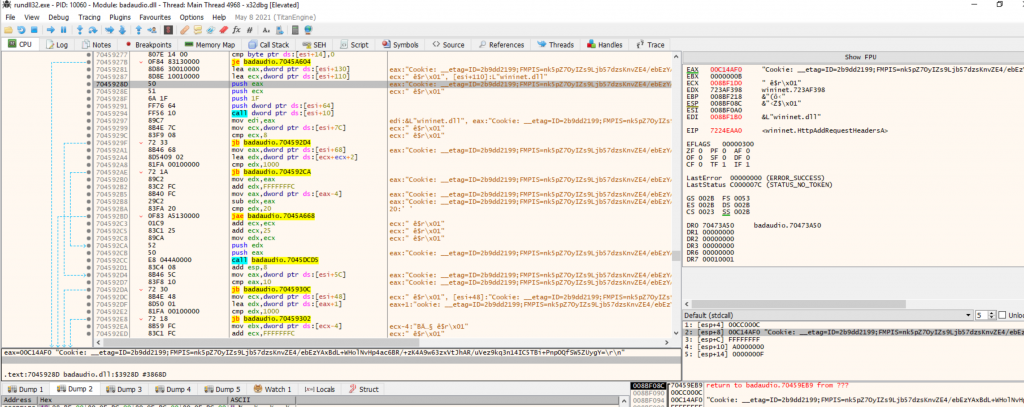

By strategically placing a breakpoint at the return function of these routines, it is possible to retrieve several of these Xored strings:

figure: strategic breakpoint to retrieve strings

Here are the decoded strings:

__etag=ID=2b9dd2199;FMPIS Cookie User-Agent Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/138.0.0.0 Safari/537.36 Edg/136.0.0.0 Accept application/octet-stream n64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/138.0.0.0 Safari/537.36 Edg/136.0.0.0 Accept-Language en-US,en;q=0.5 t-stream Cache-Control no-cache HeapDestroy VirtualFree TerminateThread ExitProcess InternetCloseHandle wininet.dll HttpQueryInfoA MtNt wininet.dll InternetReadFile wininet.dll kernel32.dll InternetOpenA wininet.dll kernel32.dll

Here I used floss to retrieve these strings all easily !

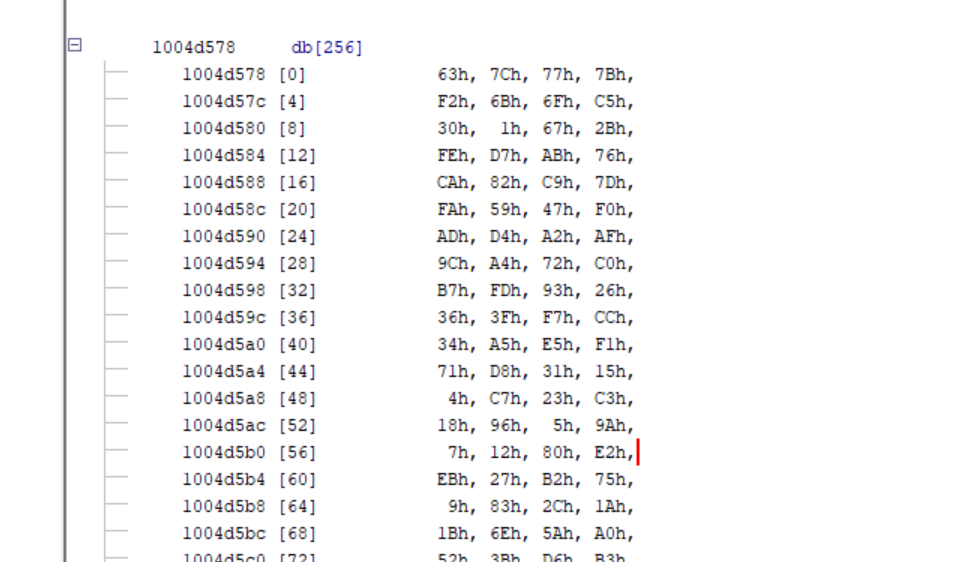

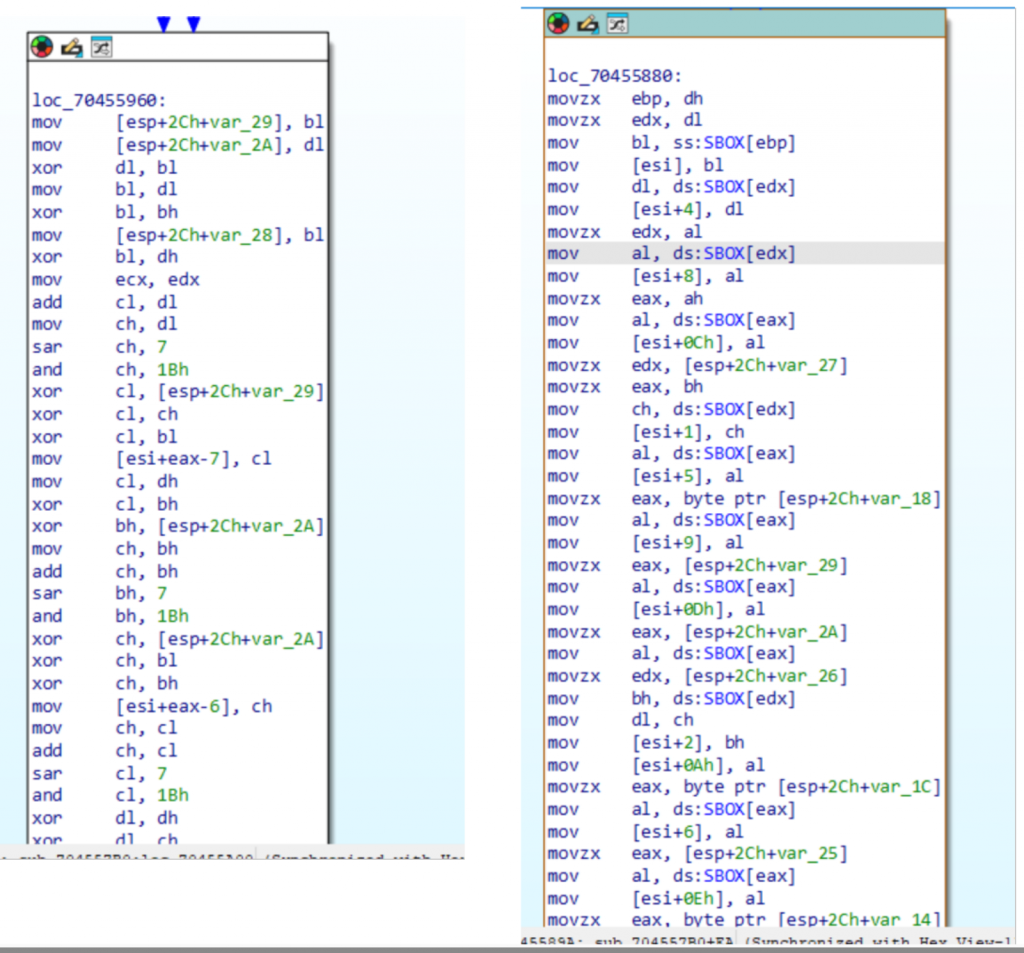

As previously reported by Google Cloud, Badaudio also uses AES encryption, notably to encrypt collected data before transmitting it to the C2 server. Several elements in the binary confirm the use of AES, including AES-specific constants and the presence of an S-box.

Figure: AES S-BOX stored in the malware

The malware embeds a 256-bit AES key in the binary as eight 32-bit constants. This key is allocated at runtime and the key material is passed unchanged to the AES key expansion routine, confirming that the encryption key is hardcoded rather than dynamically derived. The encryption routine implements AES-256 in CTR mode.

Figure: Hardcoded AES key

Because this is x86 code and these are stored as 32-bit words in memory, the byte order is little-endian per word. The 32-byte key is therefore:

b31b6db8f6f905fc9560f237c7af38515bd2a80d50e079bd1e297a1a9e94c8fe

Figure X: AES MixColumns stage (left) and AES SubBytes transformation / S-box lookup (right)

Network:

BadAudio builds and sends an HTTP request using the WinINet API. First, it creates a request with wininet!HttpOpenRequestA, specifying the HTTP verb « GET » and the object path « /v3.1/current_user/details ».

Before sending the request, the malware injects a custom Cookie: request header using wininet!HttpAddRequestHeadersA. The header contains two values, __etag=… and FMPIS=…, which include, as noted by Mandiant, an encrypted and encoded version of the information retrieve about the infected machine.

Finally, the request is transmitted via wininet!HttpSendRequestA. At the time of the send call, the malware does not provide additional headers inline (lpszHeaders = NULL) and does not provide a request body (lpOptional = NULL, length 0), indicating that the header set (including the Cookie) was pre-attached to the request handle earlier via HttpAddRequestHeadersA.

Figure: sending HTTP request with encrypted data in the cookie header

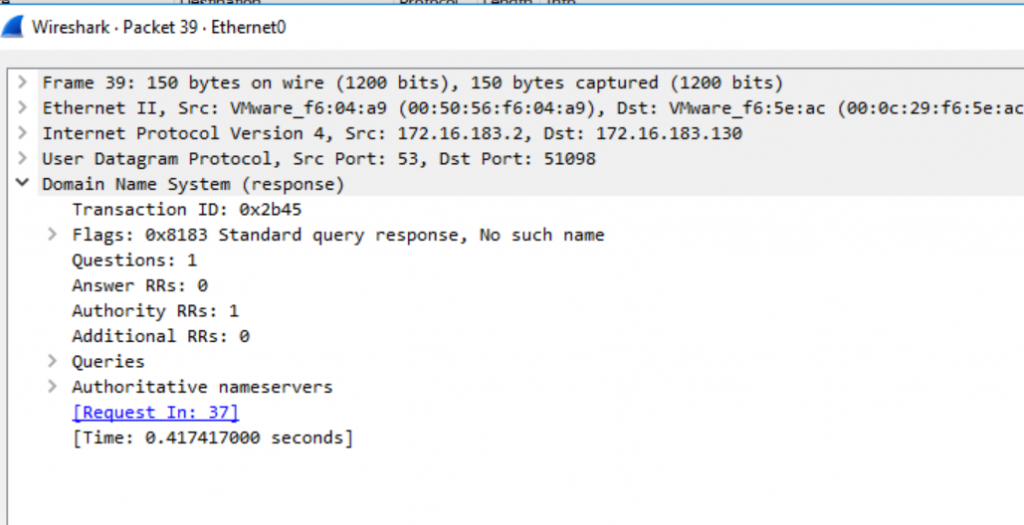

At the time of analysis, the C2 domain returned an NXDOMAIN response from the queried DNS resolver, indicating that the domain name could not be resolved.

Figure: Wireshark capture

As shown in the Wireshark capture, the DNS response contains the flag “No such name” and zero answer records. This suggests that the domain was either no longer registered, intentionally taken down, or otherwise unavailable at the time of testing.

Using Cloudflare Workers (workers.dev) can help the operator blend in with legitimate web traffic and benefit from the generally strong reputation of a mainstream CDN/serverless provider. This may reduce the effectiveness of simple, reputation-based blocklists and make domain-based IoCs more disposable (attackers can rotate subdomains easily).

While encrypting data prior to transmission may complicate network-level inspection and hinder SOC analysts from quickly determining the nature of exfiltrated data, the use of a hardcoded key significantly weakens the scheme from a reverse engineering perspective. Once extracted, the key enables offline (and potentially retroactive) decryption of captured payloads.

A good balance?

It is always interesting to analyze tools from APTs that are rarely observed in public reporting. In this case, APT24 appears to combine for its malware several “low-cost” evasive measures—XOR-obfuscating API names and strings, leveraging workers.dev infrastructure, and encrypting (then Base64-encoding) host/configuration data before embedding it in an HTTP request header. Overall, these choices suggest an attempt to balance operational security with implementation simplicity/efficiency and cost.

While Google describes the component as a “highly obfuscated loader,” the observed obfuscation is primarily geared toward evading static detection and quick triage rather than fundamentally preventing reverse engineering. Taken together, these techniques are consistent with broader reporting on the increasing emphasis on OPSEC among several China-nexus intrusion sets.

Anyway, it is likely that APT24 does not need to leverage more OPSEC to achieve its goals and that this level of obfuscation and OPSEC strike a good balance between stealth, cost and efficiency.

Anyway, APT24 likely doesn’t need to invest in stronger OPSEC to achieve its objectives, and this level of obfuscation and operational security appears to strike a good balance between stealth, cost, and efficiency.